Move 1

Lead with Western symptoms. Never name the tradition first.

The Elix website leads with outcomes, not tradition. The hero reads "Proven herbal care, tailored to your cycle," foregrounding efficacy and personalization before any mention of Chinese medicine. The color palette is warm lavender and cream. The CTA is "Discover My Formula," language that positions the consumer as the subject.12

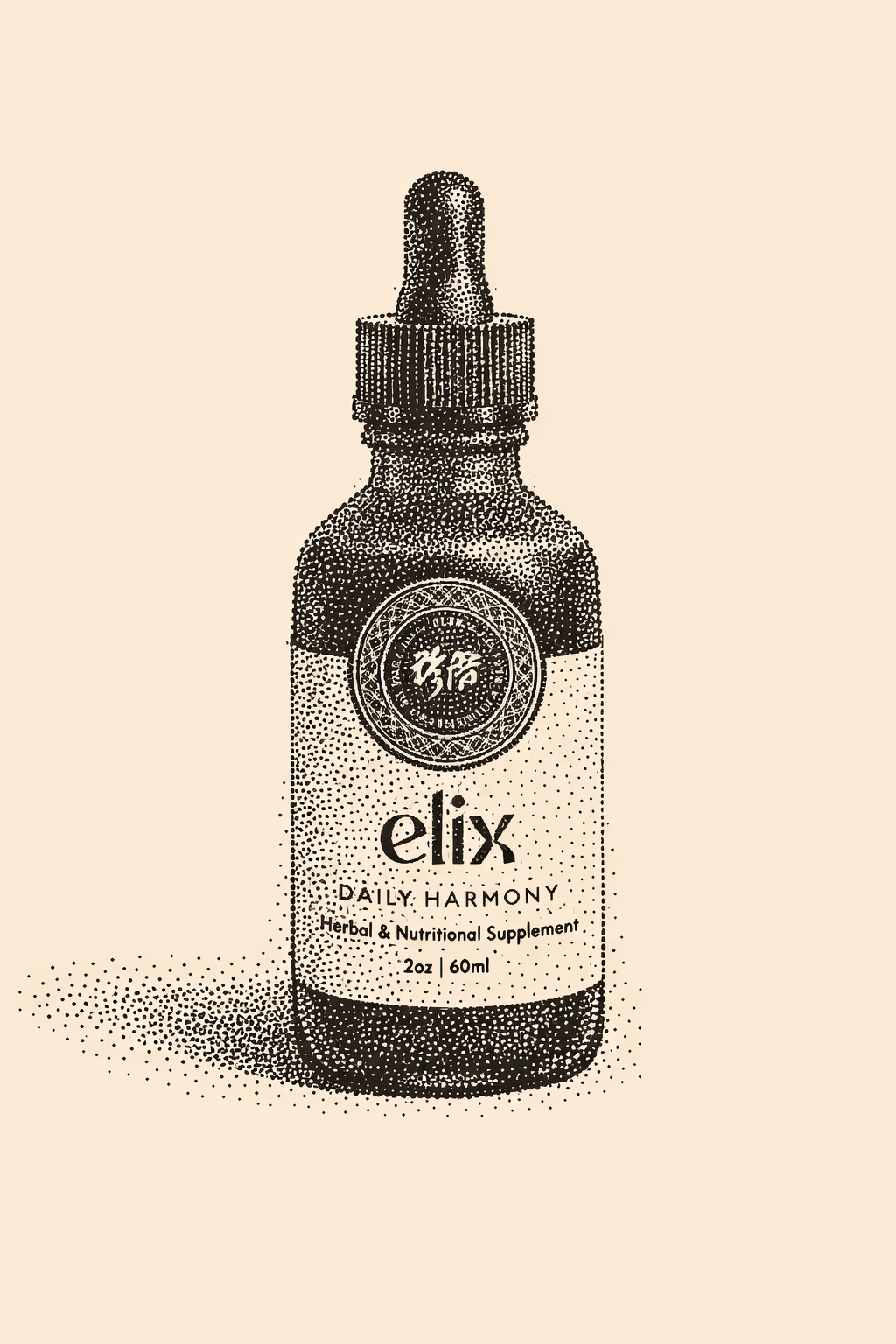

Scroll further, though, and the strategy reveals its layers. A section titled "5,000 Years of Ancient Wisdom" appears prominently, with herb photography (Dang Gui, White Peony Root, Motherwort) catalogued by Western benefit language: "menstrual harmony," "digestive support," "emotional balance." The product imagery features raw ginger, dried roots, and tincture bottles rather than the lifestyle photography typical of DTC wellness brands. Elix does not suppress its TCM identity; it sequences it, placing symptom-first framing at the entry point and tradition-first framing deeper in the scroll, after the consumer has already been given a reason to keep reading.

Research on TCM consumer adoption helps explain the sequencing. Only 45% of Americans are familiar with both acupuncture and Chinese herbal medicine. Just 30% believe TCM is comparable to Western medicine.13 Elix translates selectively rather than comprehensively: "root cause" instead of diagnostic terminology, "pattern of imbalance" instead of tongue-and-pulse language, "internal heat (inflammation)" with Western parentheticals trailing the TCM concept. The tradition is present throughout the site, but it arrives after the consumer's problem has been named in her own vocabulary.

What it solved: The entry barrier. A consumer searching "period pain relief" can find Elix without ever learning the phrase "Liver Qi Stagnation."

What it may cost: In TCM, the diagnostic language carries clinical meaning that Western equivalents do not fully capture. "Liver Qi Stagnation" and "inflammation" are not synonyms. How much of that distinction the personalization engine preserves behind the consumer-facing interface is difficult to assess from outside. There is also a regulatory dimension. Under DSHEA, Elix can claim "supports hormonal balance" but cannot claim to treat PCOS, endometriosis, or dysmenorrhea. Customer testimonials on the Elix website reference cancelling endometriosis surgery and PCOS resolving on ultrasound, which may constitute implied disease claims. The FDA issued enforcement actions against comparable companies in 2025 for this kind of language linked to purchase pages.29